Some days it seems like everyone is talking about seafood fraud. Overall, this is a positive development. Policies are being designed and revamped in attempt to reduce seafood mislabeling. And, more and more groups are testing products for mislabeling. Despite the increased attention, however, we still know very little about the causes and consequences of seafood mislabeling. Most of what we know is based on anecdotal observations and untested hypotheses.

An ACS paper in the journal Marine Policy takes a first step towards rigorously exploring the potential incentives for seafood mislabeling. It is often assumed mislabeling is primarily driven by the good ‘ole incentive of increasing profits. That is, the desire to label a lesser-value product as a higher-value one. Economic theory predicts that information asymmetry in seafood products (i.e., sellers have more information about the true quality than buyers) can motivate mislabeling. And, indeed, the mislabeling of lower-value products for more expensive ones has been documented.

What are the main results? First, useful data are scarce. Seafood mislabeling studies rarely present price data: less than 10% of studies do so. Second, current evidence suggest the causes of mislabeling appear to be diverse—it’s more complicated than often appreciated. Across all seafood products, there is no evidence for a simple mislabeling for profit driver. Overall, the difference between the price of a labeled seafood product and its substitute when it was not mislabeled is not different from zero.

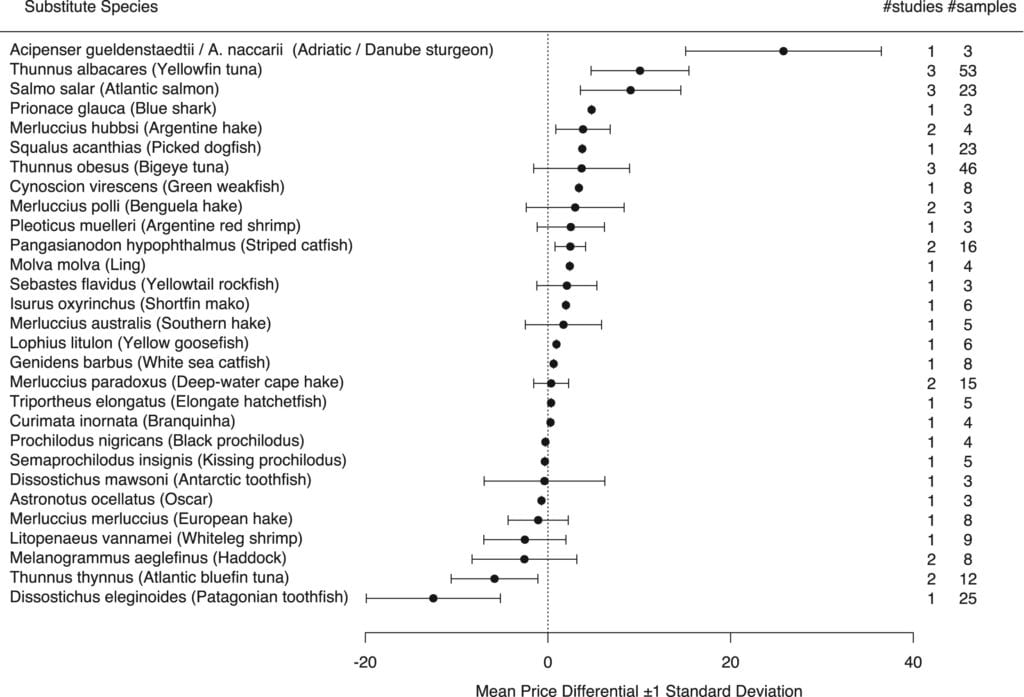

But, examining the price differential of specific seafood products provides intriguing insights into the motivations of mislabeling. Some substitute products, such a sturgeon caviar, Atlantic Salmon, and Yellowfin Tuna have a positive price differential, and may often have the sufficient characteristics to motivate mislabeling for profit. For example, Yellowfin Tuna as a substitute for other types of tuna captures a +10 euro price differential, on average. A few products, such as Atlantic Bluefin Tuna and Patagonian Toothfish, have a negative price differential. This reverse substitution (i.e., labeling a product as something that is less valuable) is an intriguing type of seafood fraud because it suggests some actors may be motivated to mislabel in order to gain market access for illegal seafood. How prevalent it is remains to be seen. Like other potential connections between IUU fishing and seafood mislabeling that have been hypothesized, little empirical evidence exist to access their prevalence or explore the details of those connections.

Mean price differential and variance pooled across studies for substitute species involved in seafood mislabeling. Species with ≥ 3 samples are included. Number of studies and samples are shown. All species consist of < 3 studies and many consists of a single study, limiting any inferences.

Most products for which there are data, however, have price differentials close to zero—suggesting other incentives are influencing seafood mislabeling. This potential list is long one: the need for the appearance of constant supply, confusing naming practices and policies, informal supply chains, mixed fisheries, and regulation avoidance are just a few. The result of our meta-analysis suggest that the causes of mislabeling are diverse and context dependent, as opposed to being driven primarily by one incentive. Given the sheer volumes involved, complex supply chains, and global nature of seafood, understanding and reducing seafood fraud is a wicked problem. Designing solutions to reduce it will likely require intricate systems-level knowledge. Price data can usually be collected easily and cheaply, and more attention to doing so could provide much needed insights into the motivations for seafood fraud. Check out ACS’s Seafood Ethics for the latest on seafood fraud.