Illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing is one of the most pressing issues impacting fisheries management and the conservation of marine biodiversity. In some cases, it contributes directly to species endangerment. More broadly, IUU activities directly inhibit the recovery and sustainable management of fisheries stocks and precipitate indirect impacts on biodiversity through unsustainable fishing practices. They are also often connected to labor abuses, as well as the loss of billions of dollars in economic benefits. Thus, reducing IUU fishing is a national priority for many countries and doing so is considered to be a high-benefit means of improving the state of many fisheries.

Yet, characterizing IUU fishing is challenging due to its clandestine nature and scarcity of data. Illegal catch is rarely, if ever, known. Current approaches to estimate IUU activity are often 1) challenging due to lack of data, 2) time- and resource-intensive, and 3) hard to replicate across space and time. Further, some methodologies have been criticized and challenged due to lack of transparency and potential biases. For many stakeholders, there is desire to complement existing IUU assessments with regular and repeatable information on illegal fishing that is attainable with limited time and resources.

A new paper by ACS and colleagues uses expert elicitation methodologies to estimate illegal fishing activity from enforcement officials in Chile’s national fisheries agency (Servicio Nacional de Pesca y Acuicultura, SERNAPESCA). Published in Scientific Reports, it provides a national illegal fishing baseline for Chile.

First, we estimated relative illegal activity for 20 Chilean fisheries, which make up ~2 mm metric tons and accounts for ~ 70% of wild capture landings in 2018. Chilean abalone (loco), followed by two species of hake, had the highest average illegal scores, while the Peruvian calico scallop had the lowest. Our results provide evidence of significant illegal activity in the small-scale fishing sector, highlighting the need to recognize and address the specific impacts of illegality on small-scale fisheries as a key component of designing solutions to reduce IUU fishing. Our results produced new information on illegal activity in Chile, including relative high estimates for red-cusk eel, southern rays bream, and anchoveta, of which the latter fishery accounted for ~ 40% of annual landings in 2018.

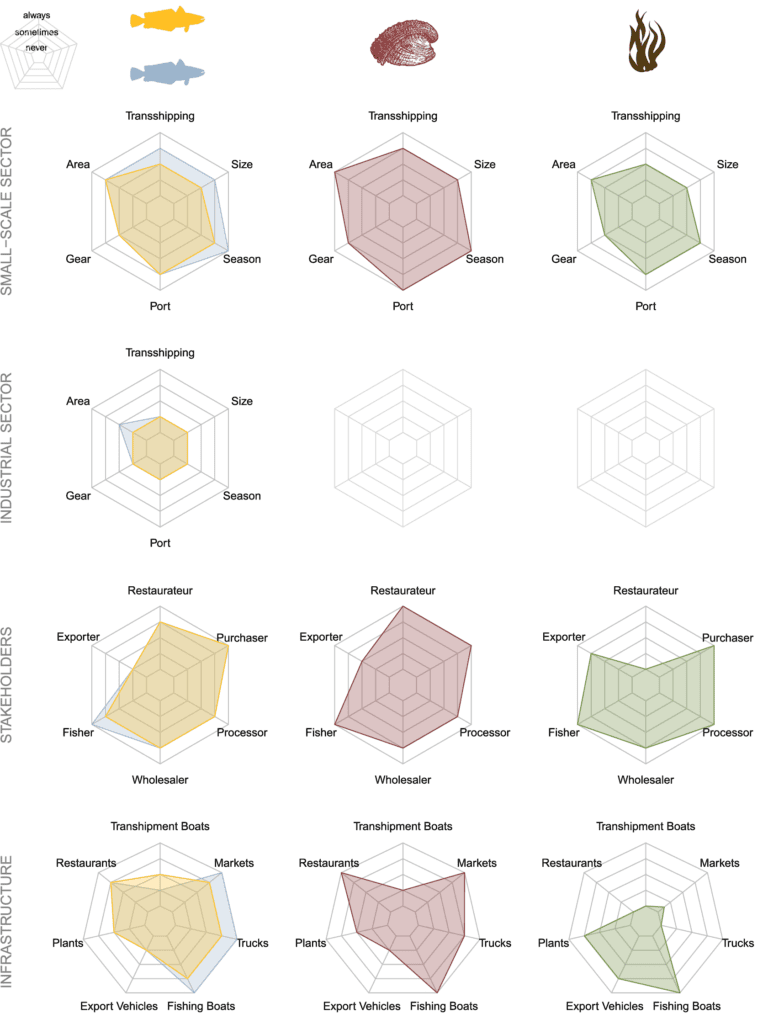

Second, we elicited additional information from respondents on four fisheries that are of particular interest in Chile with respect to illegal activity. For all four fisheries (i.e., loco, kelp, and two species of hake), >60% of enforcement officers reported that the percentage of total landings that are illegal is greater than 20%, with the most common score being 20–50% for all four fisheries. Using statistical models, we created fishery profiles that provide additional layers of information on illegal activity across stakeholders, infrastructure, and activities within sectors. For loco, for example, illegal activity appears to be dominated by small-scale fishers (fishing boats), restaurateurs (restaurants), and buyers (markets).

Fishery profiles of four Chilean fisheries: south Pacific hake (blue), southern hake (orange), Chilean abalone (red), and kelp (green). Predicted median estimates of the level of illegality in industrial sector activity, small-scale sector activity, stakeholders, and infrastructure. Industrial fishing does not exist for Chilean abalone and kelp. Predicted medians are from a Bayesian cumulative multinomial logit model for each of the four focal fisheries.

Last, we use a multivariate analysis to create a relatively simple tool to easily visualize factors that are similar and different across multiple fisheries of interest with respect to illegal activity. For example, factors associated to exporting and processing are important for kelp, while domestic factors are more important for hakes, such as markets and retail activity. The ability to use surveys to create multi-factorial fishery profiles can inform the design of specific interventions to reduce illegality, while the multivariate analysis can inform the broader IUU landscape, including the design of interventions that could have synergistic impacts on multiple fisheries.

Eliciting information from fisheries officers provides insights on how government institutions can build a knowledge base on IUU fishing activity, which can be used to shape the broader institutional context in which they operate. Our Bayesian approach provides a statistically rigorous methodology that improves parameter estimates, while also controlling for potential biases. This is particularly important for monitoring activity through time with different enforcement officers. By estimating illegal activity across activities, stakeholders, and infrastructure, our approach can help address fragmentation of knowledge that is suspected of preventing effective enforcement. Given that current approaches to measuring IUU activity can be resource intensive and sometimes controversial, estimating illegal activity directly from fisheries enforcement officers is a complementary approach that provides a cost-effective, rapid, and rigorous method to measure, monitor, and inform solutions to reduce IUU fishing.