The majority of species at risk of being listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) rely on habitat located on privately-owned land. There are lots of programs in the U.S. that seek to incentivize private landowners to manage their land to benefit at-risk species prior to any regulatory triggers, which is often referred to as prelisting conservation. Although a critical mass of participation is necessary to produce the landscape-level benefits needed for species recovery, an understanding of what motivates private landowner willingness or unwillingness to participate in prelisting conservation programs is often overlooked as a key factor in their success.

In the journal Human Dimensions of Widlife, ACS and colleagues published a study that used the Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative (LPCI) as a case study to explore the characteristics and motivations of private landowners who were willing or unwilling to enroll in a decade-long program to protect the lesser prairie-chicken. The bird’s distribution has been reduced by >90% over the past century and threats to its habitat persist. The LPCI was launched in 2010 by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) to help ranchers and farmers voluntarily enhance habitat and prevent an ESA listing while also aligning with ranching and agricultural operations. Throughout the range of the lesser prairie-chicken, we surveyed ranchers and farmers that where LPCI participants with active or completed contracts and nonparticipants from across the region. Declining participation in the LPCI was a motivating factor for our case study.

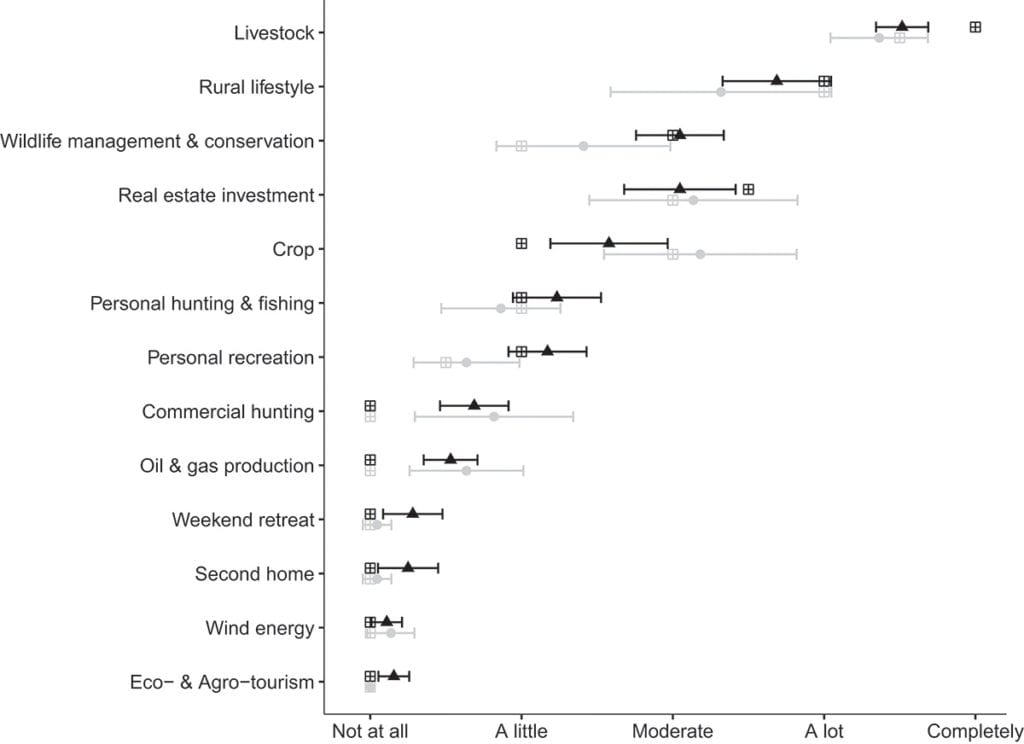

What are the main results? First, there were only minor differences between participants and nonparticipants with respect to personal and land characteristics. Most respondents were similar in their age, education, amount of income they generated from their land, and acres they managed, as well as their social networks and rootedness. Second, both groups appeared to have similar motivations and values. Both groups rated livestock, rural lifestyle, real estate investment, and wildlife management as their most important management objectives. Both groups also expressed high economic dependence on their land, that their land represented their way of life, and they had nearly identical beliefs with respect to environmental values. Third, both participants’ and nonparticipants’ awareness of events connected to the ESA and the lesser prairie-chicken were similar. And, about half of both groups stated that the ESA listing had no influence in their decision to participate or not in the LPCI.

We did some observe some differences between the two groups with respect to LPCI participation. Compared to nonparticipants, participants had a more positive attitude of the LPCI, viewing it as less risky, and expecting more positive outcomes from the program. Participants’ strongest beliefs about what would happen with participation were related to economic benefits, followed by helping future generations and helping the lesser prairie-chicken. Nonparticipants ranked giving up control, over-regulation, and the difficulty of working with the government as the strongest barriers to participation in the LPCI.

Surveyed participants (▲) and nonparticipants (●) of the Lesser Prairie-Chicken Initiative appear to have similar management objectives. Respondents rated their management objectives for their land, on a Likert-type scale, based on how well each factor described what they do with their place. Means (95% CI) and medians (⊞) are shown.

In conclusion, we identified few differences between participants and nonparticipants across personal and land characteristics, motivations and values, and knowledge and attitudes toward the ESA. This raises the question, how do similar landowners come to different conclusions about the LPCI? We consider two possibilities that would benefit from more research, and we discuss their management implications. First, program outreach may differ across contexts. Most landowners first heard about the LPCI from an NRCS officer, but these agents differed in their familiarity, experience, and opinions of the program. Program managers may be able to increase participation through increased outreach to landowners and NRCS staff training that focuses on communicating the benefits of the LPCI to landowners. Second, barriers for nonparticipants to enroll in the LPCI and the observation that most landowners distrusted the regulatory assurances provided by the program are consistent with other studies. Combined, these results suggest that independence and dissociation with the federal government may be additional factors motivating nonparticipant decisions. In such a case, efforts to decouple the LPCI from the federal government may enhance participation.

A further consideration for managers is that declining enrollment may be related to structural factors of the LPCI. Landowners with favorable attitudes and the greatest potential gains from the program may have been the first to enroll, but then phased out of the program. Participants must implement new conservation practices on their land with each subsequent contract. Thus, re-enrollment is limited and the program relies heavily on recruitment. Our research highlights the need to identify other factors that motivate or inhibit participation, such as outreach, program structure, or other landowner values.